Get Ready For the New, Improved Second

Scientists are preparing to redefine the fundamental unit of time. It won’t get any longer or shorter, but it will be more precise — and a whole lot more powerful.

Modern civilization, it is said, would be impossible without measurement. And measurement would be pointless if we weren’t all using the same units.

So, for nearly 150 years, the world’s metrologists have agreed on strict definitions for units of measurement through the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, known by its French acronym, B.I.P.M., and based outside Paris.

Nowadays the bureau regulates the seven base units that govern time, length, mass, electrical current, temperature, the intensity of light and the amount of a substance. Together, these units are the language of science, technology and commerce.

Scientists are constantly refining these standards. In 2018, they approved new definitions for the kilogram (mass), ampere (current), kelvin (temperature) and mole (amount of substance). Now, with the exception of the mole, all of the standards are subservient to one: time.

The meter, for example, is defined as the distance light travels in a vacuum during one-299,792,458th of a second. Likewise, the new definition of the kilogram rests on the second, in a manner too complicated to explain in fewer than several paragraphs.

“All the units now are not autonomous units, but they are all depending on the second,” said Noël C. Dimarcq, a physicist and the president of the B.I.P.M.’s consultative committee for time and frequency.

That means that conceptually, if clumsily, you could express other units, such as weight or length, in seconds.

“You go to the grocery and say, ‘I would like not one kilogram of potatoes, but an amount of seconds of potatoes,’” Dr. Dimarcq said.

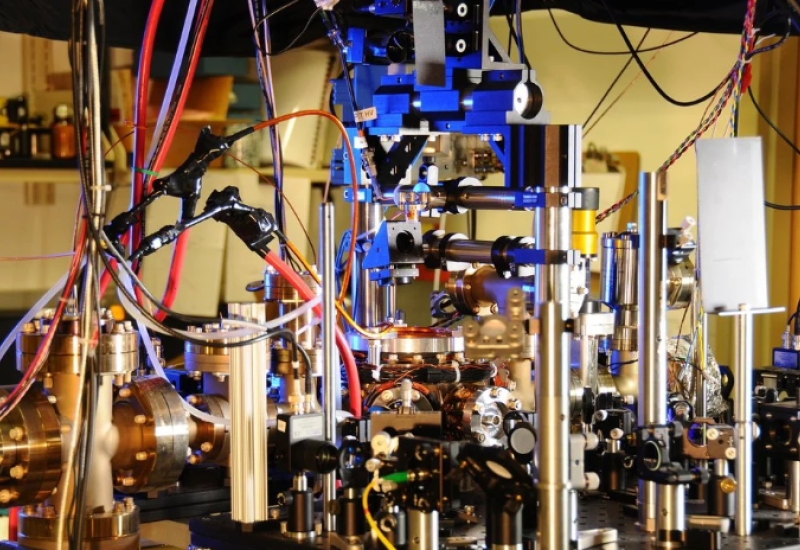

Yet now, for the first time in more than a half-century, scientists are in the throes of changing the definition of the second, because a new generation of clocks is capable of measuring it more precisely.

In June, metrologists with the B.I.P.M. will have a final list of criteria that must be met to set the new definition. Dr. Dimarcq said he expected that most would be fulfilled by 2026, and that formal approval would happen by 2030.

It must be done carefully. The architecture of global measurement depends on the second, so when the unit’s definition changes, its duration must not.

Once, humans told time by looking at the heavens. But since 1967, metrologists have defined time instead by measuring what’s going on inside an atom — clocking, as it were, the eternal heartbeat of the universe. Atoms never wear out or slow down. Their properties do not change over time. They are the perfect timepieces. (By the middle of the 20th century, scientists had coaxed atoms of cesium 133 into divulging their secret inner ticks).

Despite that cesium-based definition, astronomical time and atomic time are still inextricably conjoined. For one thing, atomic time occasionally needs to be adjusted to match astronomical time because Earth continues to change its pace at an irregular rate, whereas atomic time remains constant.

And scientists are looking once more to the heavens for help. Now, though, it’s not to track the movements of planets or stars, but to use information from far beyond our galaxy.

Source: The New York Times

Image: Burrus/NIST