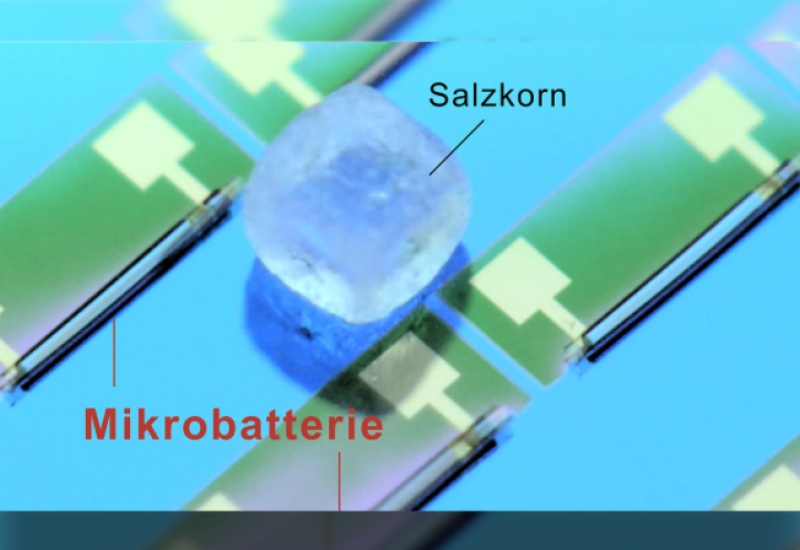

World's smallest battery assembles itself like a Swiss roll cake

The ongoing miniaturizing of electronics calls for an ongoing reimagining of the devices that power them, and a new example from scientists at the Chemnitz University of Technology has taken this technology into tiny new territory. By deploying what's described as a Swiss-roll-inspired self-assembly process, the researchers have produced the world's smallest battery, which they say could find use in powering small sensors in the human body, among other applications.

The groundbreaking energy storage solution was created through what's known as the Swiss-Roll process, inspired by the spongey cylindrical cakes rolled up with thick layers of jam inside. But instead of turning to sugar and flour, the scientists layered current collectors and electrode strips made of polymeric, metallic and dielectric materials onto a tensioned wafer surface.

Peeling off these individual layers sees the tension released and the materials snap back, rolling up around each other to take on the same architecture as a Swiss roll cake to create a "self-wound cylinder micro-battery." This device is smaller than one square millimeter across and around the size of a grain of dust, with a minimum energy density of 100 microwatt hours per square centimeter.

These attributes make the battery suitable for eventual integration into tiny chips with electrical circuits, according to the researchers, which could take the shape of biocompatible sensors in the human body.

Many of these types of sensors rely on harvesting methods to generate electricity, for example turning mechanical vibrations into energy, or capturing heat for the same purpose. But this won't work in all scenarios, such as inside the human body. The scientists see their type of rechargeable micro-battery, which they say could power the world's smallest computer chips for around 10 hours, as a solution to this problem. Other possible applications include robotic systems and ultra-flexible electronics.

"There is still a huge optimization potential for this technology, and we can expect much stronger microbatteries in the future," said Professor Oliver Schmidt, who led the research.

Source: New Atlas

Image: TU Chemnitz/Leibniz IFW Dresden